Duality in Design

When a Cameroonian designer and artist immersed himself in Japanese culture, he found commonalities in tradition and heritage between two sides of the world. Enter the African-Japanese kimono – a hybrid garment created to celebrate identity and inheritance, unconventionality with a shared sense of belonging, and a new aesthetic.

“Make haste slowly, and without losing heart, return a score of times to perfect your art.” The seventeenth-century French poet Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux’s words resonate with the artist-designer Serge Mouangue, the creator of a hybrid type of kimono that fuses cultural traditions from different parts of the globe. As Mouangue himself puts it, “In this work I am fascinated by the constant search for perfection. The time spent composing, trying, trying again, improving.”

Serge Mouangue was born in 1973 in Yaoundé, the capital of the West African country of Cameroon, but his parents emigrated to France when he was 6, and he was brought up in the banlieues of Paris. His father was keen for him to become a lawyer or an engineer, but an early talent for drawing took Mouangue instead to art school, then to study industrial design at ENSCI, the French national institute for advanced studies in industrial design, from which he graduated in 1999. A keen traveler, he spent his student years exploring France and visiting other parts of Europe, as well as venturing farther afield to Turkey, China, Mexico, and the USA. During a placement year in Australia, he interned with the architect Glenn Murcutt, who in 2002 won the Pritzker Architecture Prize. Also while there, Mouangue met and married his wife, and they had their first child.

Returning to Paris in 2000, Mouangue joined the concept-car design team at Renault’s Technocentre, but in 2006, thanks to Renault’s co-partner, Nissan, he got the opportunity to move to Japan, working in Nissan’s Creative Box studio in Tokyo. He lived in Japan for the next five years, and the country and its culture was to be a revelation to him. As a Cameroonian in Japan, Mouangue was struck by the similarities between his homeland and the land of the rising sun. “Of course,” he admits, “Japanese society is by nature rather strict, whereas in West Africa, improvisation is a form of survival. That being said, however, there is a great deal of common ground between the two identities. For example, the younger generation’s relationship with the elders is a cornerstone of both cultures. Japan has avery codified and hierarchical tradition. As in West Africa, the way in which you address a person will vary depending on whether it is a man or a woman, a person of expertise or not, or someone old, very old, or young.

“I also noted the relationship to the dead that exists in voodoo practice and the relationship to ghosts that is omnipresent in Shinto culture. In aesthetic terms, Punu masks [ from Gabon, Central Africa, and often covered with a layer of kaolin clay] remind me of Japanese Noh masks. All of this led me to develop a language that I called my ‘third aesthetic,’ which does not really belong to either culture. It carves out a new path concretized by performance, clothing, sculpture, and visual arts.”

After returning to France and Renault’s Technocentre, Mouangue continued to develop his third aesthetic. Then, by 2016 he was ready to leave the world of car design. Meanwhile, visits to Kyoto saw him develop a growing interest in the ne plus ultra of Japanese traditional clothing, the kimono. “Kyoto is the birthplace of the kimono. It is the most natural thing to wear in Japan. In Japanese, kimono comes from ki (to wear) and mono (the thing).”

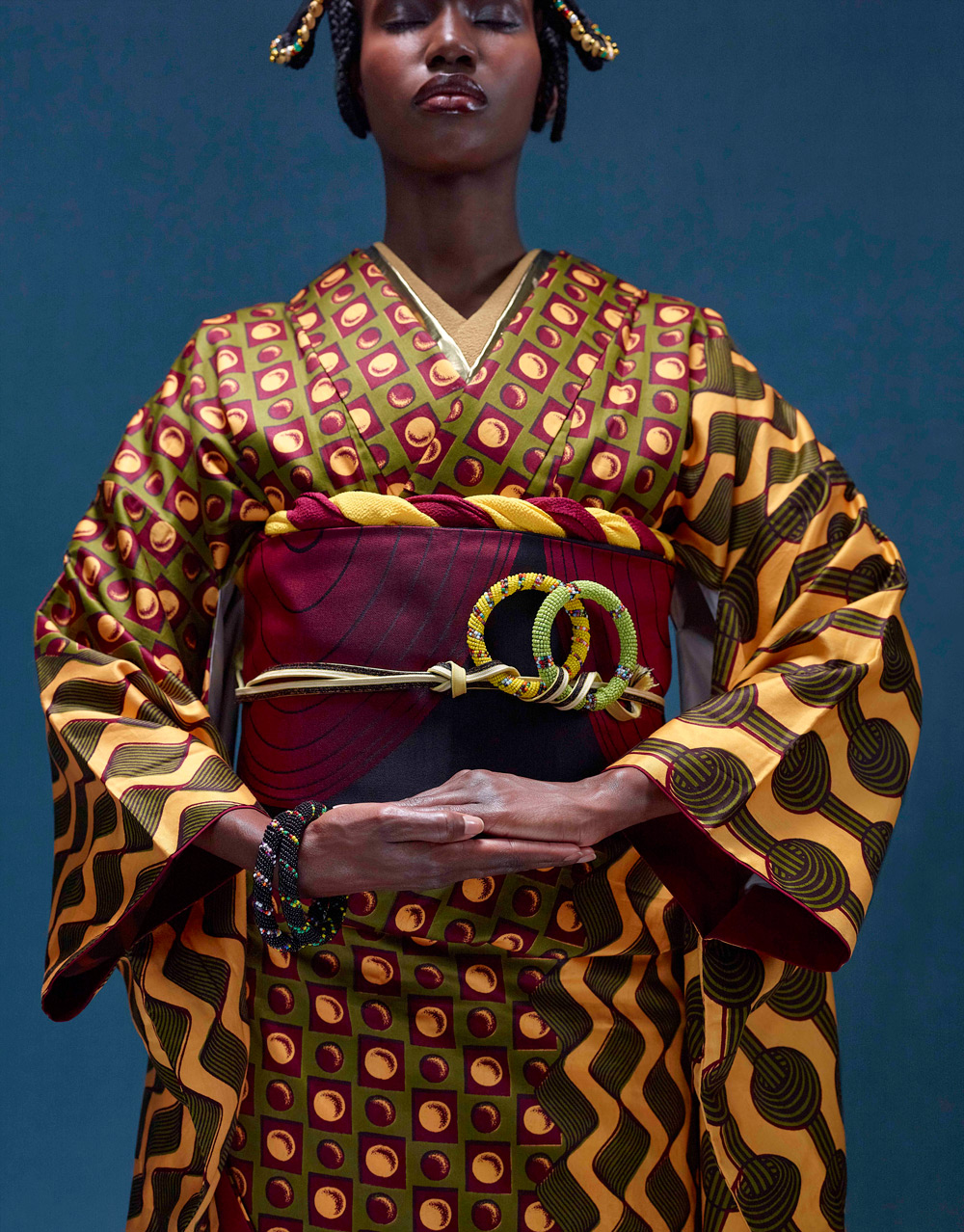

Serge Mouangue’s kimonos are hybrid creations that fuse the cultures of Africa and Japan. The fabric of the blue kimono (page 44) was patterned by the loincloth wax technique, inspired by Javanese batik. It is paired with an obi from Kyoto made of crafted silk. The obi-age, knotting the obi in place, is made from kente, a woven cloth from Ghana. The brown kimono was inspired by the earth.

Made from traditional bogolan fabric dyed with an extraction of African birch leaves, or n’galama, it features a design drawn with fermented mud. The lining of the kimono coat, or haori, is embroidered in a style from Mauritania. A wooden hair comb from Cameroon completes the outfit. The print of the loincloth wax kimono shown above was inspired by electric circuits. The obi is made of fabric from Kenya, the traditional Maasai Shuka, also known as “African blanket”

In order to steep himself in the culture of the kimono, Mouangue went to learn from traditional manufacturers. “I wanted to understand not only the history of this garment but also its codes, its cut, its proportions, its assembly, and also the use of accessories, of which there are a great number. I began by working with Kururi in Tokyo and then Odasho in Kyoto. The kimono is a complex garment to put on because of its system of folds. It can take up to an hour if you want to arrange it properly. This correct way of putting it on is ultimately just as important as the material it is made from. The method of belting the garment in place with an obi [the traditional belt] and the way the obi is tied are also highly sophisticated.”

Mouangue’s own unique contribution to all this was to create kimonos using unconventional textiles. He uses African fabrics such as bogolan (a traditional Malian cotton fabric made up of strips sewn together and dyed with earth), wax prints (a sub-Saharan African type of cotton material that is made with batik-inspired printing), and ndop (a fabric from the Bamileke people of Cameroon, made up of strips of fabric decorated with geometric figures in white and blue). “Fabrics from West Africa are extremely rich,” explains Mouangue. “I use them in combination with silk obis from Kyoto to create this mixture of genres, this third aesthetic. We spend a lot of time on kimono designs. Some of these kimonos are made to be displayed, others are to be worn.” Mouangue works mainly with the house of Odasho in Kyoto, a family-owned firm that has been making kimonos for more than one hundred years. As a designer, Mouangue’s job could be described as that of composition. “At Odasho, my work consists of procuring fabrics and making kimonos with patterns that are repeated harmoniously on the garment. Achieving harmony between the cut and the pattern takes great precision. I also take great care with dyeing the silk for the obis in Kyoto water, which in the Japanese tradition is considered to be the purest.”

But the designer’s African identity is never far away. He says that in order to gain acceptance in the traditional structure of Japan’s culture he chose to act according to the tradition of his birth rather than behave like the Japanese person that he is not. And this worked. As he explains, “[In Japan] it was very important to respect the hierarchical systems to the letter, using the body language I was taught as a child.”

Marrying the kimono tradition to the cultures of West Africa was quite a gamble, but it proved a highly successful one. The turning point came in 2008 when the Japan Times devoted a major article to Mouangue’s work. Things snowballed after that. The Museum of Art and Design in New York commissioned him to design another hybrid work that combines the technique of Japanese lacquer with Pygmy sculpture. His work is also increasingly seen abroad. In 2020 London’s Victoria and Albert Museum devoted an exhibition to kimonos and included some of Mouangue’s designs.

His works in the collection also featured in a BBC television program about the museum. In 2022 another invention of his third aesthetic will be exhibited at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris. In this new piece, Mouangue will make a connection between the weaving of Japanese ikebana baskets and the hairstyles of peoples in West Africa. Today, Japanese people, too, have begun to wear his kimonos, attracted by their unusual patterns and lighter, less constricting fabrics. “One good thing about them is that they provide a certain freedom,” Mouangue explains. “People like to use my kimonos, because they escape some of the etiquette of the Japanese tradition.” Perhaps his third aesthetic shows a new way forward for an ancient tradition.

Artist: Serge Mouangue

Story: Judith Benhamou-Huet

Stills: Silvia Draz

Translated by Charles Penwarden